The “5% Problem”: Why Students Don’t Engage In Tutoring Enough (And How To Fix It)

By Danielle Thomas

Now more than ever, tutoring providers, researchers, and big edtech are in a race to leverage artificial intelligence (AI) to help K-12 students learn math. From student-facing chatbots and AI assistants to tutor copilots, the field is rich with promising solutions to improve student engagement and learning.

This is an opportune time for human-AI synergy to enter schools, as stakes have never been higher. The NAEP reports 8th grade math progress remains flatlined and 12th grade scores are the lowest ever reported. The dire need for math support has created a rich climate for tutoring providers and edtech companies to dive into the trenches with teachers and schools to help kids learn.

The Learning Engineering Virtual Institute (LEVI) is a large-scale independent institute established by Renaissance Philanthropy with a mission to drastically improve education outcomes by leveraging AI. The goal of the LEVI Math program is to double the rate of math learning for middle school students, especially those from low-income backgrounds.

Presently, there are seven LEVI Math-supported teams:

- Khanmigo, Khan Academy’s AI-powered, chat-based tutor

- PLUS, a human-AI tutoring program from Carnegie Mellon University

- Eedi, a UK-based student learning app providing math misconceptions support

- MATHstream, an interactive video streaming platform from Carnegie Learning, Inc.

- ALTER-Math, an AI-augmented teachable agent embedded in Math Nation

- HAT, a hybrid human-AI tutor from the University of Colorado Boulder

- Rori, WhatsApp-based tutor chatbot lead by the Rising Academy Network

These teams may provide AI-assisted math support to students in differing ways, from student-facing chatbots to human and AI teaming platforms, to teachable agents. However, their mission is one and the same: doubling student learning among those who most need it. Despite this common goal, a persistent and all-too-known challenge threatens to undermine these innovations: student usage.

New Tech, New Opportunities to Attend to the Usage Problem

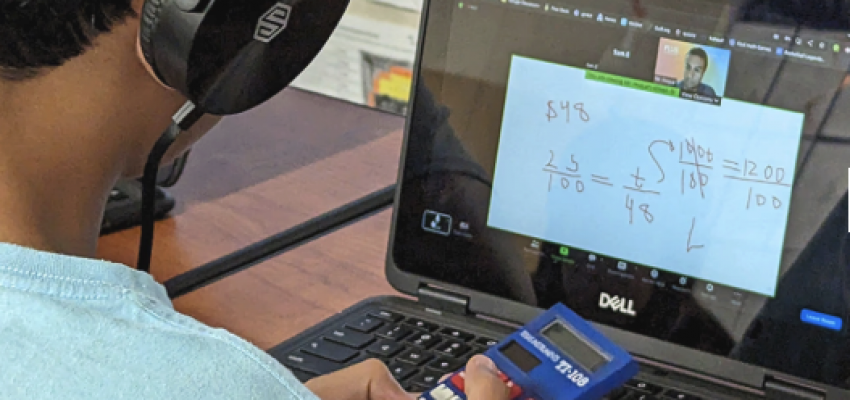

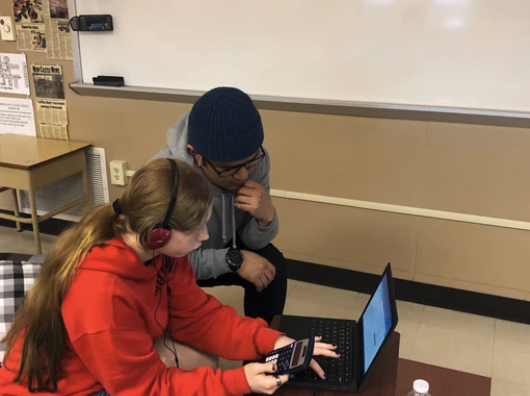

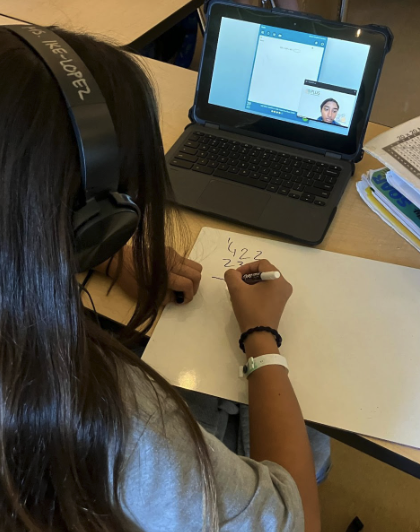

A case in point is PLUS, a hybrid human-AI tutoring program and LEVI-sponsored team. PLUS brings human tutors remotely into schools to provide math help while students work on widely-used math edtech platforms like IXL, Curriculum Associates’ i-Ready, and Carnegie Learning’s MATHia. While PLUS has demonstrated positive effects on student learning over its three years, the team is now exploring strategies to further enhance its impact and scale the gains. The hybrid human-AI tutoring intervention has proven to be a less costly (four times lower to be exact) and more scalable solution than traditional one-on-one human tutoring. However, PLUS is focusing on increasing dosage, or the amount of time students are engaging with the tutoring. Many students, despite participating in tutoring at least 1-2 times per week, are not spending enough time or completing enough math problems, or as the PLUS principal investigator and Carnegie Mellon University professor Ken Koedinger would say, engaging in enough focused and deliberate practice.

A similar story is emerging from Khan Academy’s Khanmigo. Introduced in 2023, this AI-powered chatbot acts as a tutor and teaching assistant, providing learners instant feedback and step-by-step guidance in math. In a pilot program, which reached 250,000 students and 450 school districts, the AI-driven chatbot demonstrated its potential to support student math learning. However, according to Khan Academy’s Chief Learning Officer, Kristen DiCerbo, a consistent challenge has been ensuring students use the tool enough to see strong gains. Its flagship program Khan Academy, which launched in 2008, has logged more than 9 million users and reports that a mere 5% of students using the system demonstrate the recommended usage of 30 minutes per week–the amount of time found to be predictive of statistically significant learning gains on standardized tests.

While low student engagement and dosage in edtech is a long-standing issue, Laurence Holt recently gave it a name: “the 5 percent problem.” The term describes the small fraction of students who use a tutoring system or learning technology with enough consistency to show learning gains. More worrisome, Holt argues, is that these are often the same students who would likely succeed anyway, regardless of the technology. For this motivated group, Holt states ‘good ole’ pencil and paper would likely be effective.

Focusing on the other 95% is precisely where hybrid human-AI tutoring systems may hold an advantage. By integrating a human tutor, systems like PLUS can focus on reaching the students who fall outside of that motivated 5%. However, despite the advent of sophisticated edtech with shiny AI features and systems, the fundamental challenge of ensuring sufficient student usage to the students who most need it remains. Dosage isn’t just about ensuring students “hit” a certain number of minutes or complete a set amount of math problems, it’s about ensuring individual students are getting the level and amount of support and deliberate math practice they need to learn math.

Eedi, a UK-based math learning platform and LEVI team, offers a different perspective on the dosage challenge. The platform diagnoses and remediates student misconceptions through targeted diagnostic questions, then provides tailored support. Unlike the 5% usage patterns reported elsewhere, Eedi sees approximately 50% of students achieving the dosage threshold of around 120 questions per year; or about 10-15 minutes of practice per week. A 2024 independent RCT involving 2,901 students across 20 schools found that students reaching this threshold showed an effect size of 0.34; equivalent to four months of additional progress. However, Eedi’s data reveals a more nuanced challenge: student engagement is not equally distributed. Students from low-income backgrounds are less likely to reach the dosage threshold (37.8%) than their more advantaged peers (53%). In other words, solving the dosage challenge reveals a harder question: are the students who most need the tool the ones actually using it? Students from low-income backgrounds are less likely to reach the dosage threshold than their peers, making the equity dimension of the usage problem especially urgent to address.

Converging Solutions Among Tutoring Providers

Educational AI developers and tutoring providers are actively tackling this challenge and independently coming up with strikingly similar solutions. The strategies being developed by LEVI teams like PLUS, Khanmigo, and Eedi will seem very familiar to teachers and students on the ground.

PLUS, for instance, has embedded a student goal-setting feature where students collaborate with their teachers and tutors to set weekly goals within an AI-driven system. A pilot of PLUS’ goal-support feature has shown promise, with students spending 25% more time on the platform and acquiring 40% more math skills. By acquiring more skills within the same amount or less time, students are not only increasing their dosage, but also the quality of the dosage. At the same time, data-driven feedback led students to set goals that they are 80% more likely to achieve than goals set by their teacher. Upon goal completion, teachers provide rewards, and PLUS works with teachers and schools to determine adequate rewards. Collaborative goal setting between teachers and students in school and remote tutors who can see students’ progress within the AI-driven math software has been shown to be an innovative method of providing more scalable and cost-effective approaches to helping kids learn math. This approach is particularly effective when a student’s individual goals in the math tutoring system are directly aligned with district-level goals. For instance, a student might set increasingly challenging micro-goals to get closer to completing 45 minutes of personalized math instruction per week, directly supporting a district-wide goal for 95% of K-8 students to meet that same time commitment.

Khanmigo is pursuing a similar strategy, recognizing that the tool’s effectiveness hinges on its integration within the school’s existing ecosystem. This point was emphasized by Khan Academy’s Chief Learning Officer, Kristen DiCerbo. In her keynote at the Artificial Intelligence in Education Conference, DiCerbo explained that Khanmigo is moving beyond relying solely on the app to motivate students. In response to student usage being lower than the suggested five or more interactions every two weeks, they are now focusing on better embedding the tool into the fabric of the classroom. This involves empowering teachers to deliver classroom-based rewards and actively linking Khanmigo usage to district-wide initiatives and programs. In addition, Khan Academy has found that there are key system elements that predict whether a school will move past that 5% usage threshold. Specifically, schools that have greater usage: 1) are using Khan Academy specifically to solve an academic problem (such as math proficiency) as opposed to just wanting an AI tool, 2) set district-level goals for learning on the platform and track progress toward those goals, and 3) dedicate time to practice in the school schedule. The promising early results from this approach validate the strategy: when the system is aligned on goals, teachers orchestrate the reward systems, student engagement with Khanmigo increases, demonstrating the critical synergy between AI technology and established school structures.

Eedi’s approach to engagement centers on treating teachers as core partners. The platform deploys targeted nudges on teacher dashboards—showing educators exactly how far their students are from achieving dosage thresholds and providing goal feedback that empowers strategic intervention. This positions formative assessment completion as a shared responsibility between platform, student and educator. Students earn streak points and coins for effort and quiz completion, and class leaderboards provide additional motivation. But the architecture keeps teachers at the center of the engagement loop.

Yet, AI-driven learning technologies, like chatbots and smart assistants by themselves are not the panacea of learning. Building better AI-driven edtech alone will not narrow learning gaps, but building AI tech in collaboration with schools and teachers will. This key takeaway is strongly supported by implementation science, the study of how to effectively integrate evidence-based practices into real-world settings like schools. Research in this area consistently shows that even the most promising interventions fail if they are not thoughtfully embedded within an organization’s existing social context. Implementation science moves beyond simply creating a tool to understand the “how” and “why” of its adoption, emphasizing the critical role of factors like teacher buy-in, alignment with school goals, and integration into daily routines to ensure new programs are used effectively and sustainably. The challenges faced by these AI-tutoring platforms are a classic example of the research-to-practice gap that implementation science aims to solve.

Attending to the 5% Problem: Integrating into School Ecosystems

A clear pattern emerges when looking at the solutions from PLUS, Khanmigo, and Eedi to solve the “5% problem,” technology must integrate with, not ignore, the existing school ecosystem. This approach requires navigating what implementation scientists refer to as the “inner and outer context” of a school. The inner context—the school’s culture, teacher practices, and classroom routines—is addressed when teachers are given the agency to set goals and manage reward systems, weaving the technology into their daily instruction. Simultaneously, these tools must align with the outer context, such as district-wide proficiency goals and scheduling constraints, to gain administrative support and dedicated time for use.

However, local implementation is not a panacea, and if not managed carefully, it can lead to disappointing or uneven results. It is not enough to simply adopt a program; there are productive and unproductive ways to integrate it. A 2024 study on Metro Nashville Public Schools’ large-scale, district-operated tutoring program provides a sobering example. Despite a well-resourced effort to scale tutoring to over 6,800 students, the study found that while the program had a positive effect on reading scores, it had no average effect on math scores. The research suggests that local implementation choices contributed to these mixed outcomes. For instance, the district used a standardized, grade-level curriculum that was less effective for students who were significantly behind and needed more foundational support. Furthermore, as the program scaled, logistical challenges shifted much of the tutoring to before and after school, altering it from a core academic intervention to a supplemental one. This case demonstrates that the crucial challenge is not just mandating a solution, but ensuring its productive application in the inner and outer contexts. The common thread in effective programs is a significant shift away from a purely student-facing tool and toward a system that empowers educators. Whether it’s teachers and tutors setting goals with students at PLUS, the teacher-led reward systems of Khanmigo, or the school-wide math competitions with Eedi, each provider has recognized that the key to engagement lies in giving teachers the agency to weave these tools into their classroom culture and initiatives.

In October 2025, Susanna Loeb, Executive Director for the National Student Support Accelerator at Stanford University, and Monica Bhatt, Senior Research Director at the University of Chicago Education Lab, Monica Bhatt outlined several tutoring non-negotiables for effective in-school tutoring. Summarized from their brief on designing tutoring programs, they state that tutoring must: occur at least three times per week, take place in small groups (ideally 1:1), be provided by trained tutors who receive continuous support, and align with core classroom instruction. Perhaps, another non-negotiable for implementing impactful tutoring should be tutoring must be deeply integrated into the school’s ecosystem, the inner and outer contexts, ensuring it is not seen as an add-on to core instruction or supplemental program, but as an integral part of normal educational practice.

What does it mean for tutoring to be a core part of the school ecosystem? First, the AI-assisted tutoring program must be selected to address a specific academic challenge identified by the district. Since most school districts operate under 5-year strategic plans with SMART goals (see example), such as ‘increasing 8th-grade math proficiency by 5% annually’, the tutoring solution must directly support that objective. Second, the tutoring platform’s metrics must align with the district’s goals, allowing administrators to track relevant progress. Third, the required ‘dosage’ must be determined in advance, with time dedicated specifically during the school day. Edtech must align with school district goals, provide metrics for school leaders to easily assess progress toward school goals, and be strategically embedded into a child’s school day–not a supplemental add-on.

Building better AI edtech alone will not narrow learning gaps. The crucial element is building AI tech in collaboration with schools and teachers. Instead of providing a tool that operates in isolation, the most effective approaches tap into the programs and initiatives that already make a school run. Lasting gains are achieved by rightly placing the teacher and the student—not the technology—at the center of the learning process.